The Helliconia Trilogy

…is 30 years old this year (2012). To celebrate here are some collated web clips and comments, starting with a word from The Grandmaster himself, on his quest for writing the definitive book, Helliconia – a definitive statement on humanity.

Helliconia Animation

Next up is a wonderful new video tribute from a young man aware of his fathers’ passion for Brian’s Helliconia trilogy, narrated by machine over a wonderful animation:

Tom Shippeys’s Introduction to Helliconia

Brian also wanted me to share an introductory piece to Volume One written by Professor Tom Shippey. It features in the leather-bound, gold-tooled edition from the US (Easton Press edition):

Helliconia Spring is more than a theme or metaphor… It is also an intensely exuberant book, full of sense of sap returning, packed with memorable images: the disastrous charge of the phagors into the super-cooled lake, Latainla Ay riding through Embruddock on a flaming stungebag, the girl Oyre discovering for the first time that the furs and skins can be shed. Even the phagirs have their own individual character: a recurrent theme of pathos is the fate of the old slave Myk, ridden like a horse by his human child-masters, in the end discarded and killed by now adult children. Two further related universes are the world of Avernus, the observation satellite from Earth poised in the sky to relay pictures of the Helliconian drama across space, its crew hesitating still over whether to intervene in that drama; and the subterranean world of the “gossies” and “fessups”, the ghosts of dead Hellconians, still capable of being visited (like the ghosts of Homer) by their living descendants demanding knowledge or advice, but creating a counterpoint of decline and oblivion to the theme of growth and new life on the surface.

Helliconia Spring is a triumph pf the imagination, a work of enduring depth and richness which demands reading and re-reading to take in its epic scale, its ironic intelligence, its commitment to dynamic change.

Helliconia Reader Reviews

Still wondering whether you should take the time to read Brian’s wonderful Helliconia Trilogy? Try these 3 latest Amazon reviews for size:

I have recently read all three volumes in the Helliconia Trilogy and was blown away by the sheer scope and imagination that Aldiss possesses. These really are an amazing set of books. I have read Hothouse and Non Stop also by Aldiss which I also rate very highly.

Will not detail the synopsis as other reviewers have done this more eloquently than I could.

“Hellicona”- a title sadly missing from the sci-fi classic masterworks series is simply one of the best works of the genre you are ever likely to read.Forget about your Greg Bears,your Arthur C Clarkes, et al and make sure you read this book.For sheer scope of setting ,imagination, it dwarfs them all.This is one of those books that make you feel a sense of your own fleeting existance in the face of the time spans covered.It contains momments of true wonder,(witness one characters finding of an LCD watch from an alien culture,Earth,and the explanations as to what it is.) granduer,and strangeness.If you only buy one sci-fi book this year make sure it is this one, for here is a book that need not be self-conscious when the title of classic is pinned to its lapels.

I read this trilogy many years ago and it still lingers on in my memory of favorite fantasy writing. I won’t try to compare it against another great series, Dune, as it is completely different, but I will say I enjoyed this tremendously and as much as the aforementioned. As previous reviewers have stated this is a ‘big’ read and requires an investment of patience early on for which the reader is subsequently rewarded. I don’t know how successful Helliconia has been but it deserves a lot more recognition, I feel. Perhaps one day it might be made into a Film trilogy. If I had time on my hands I would re-read it !

Brian writes about the creation of the Helliconia Trilogy

HELLICONIA: HOW AND WHY

FOR MANY YEARS I HAD CONTEMPLATED WRITING A STORY about a world where seasons were so long that all one’s life might pass in spring, say, or in the winter. The idea had a powerful emotional appeal. Some while ago, I walked into a Northern town and discussed this idea with another writer, Bob Shaw, who was also powerfully attracted to it.

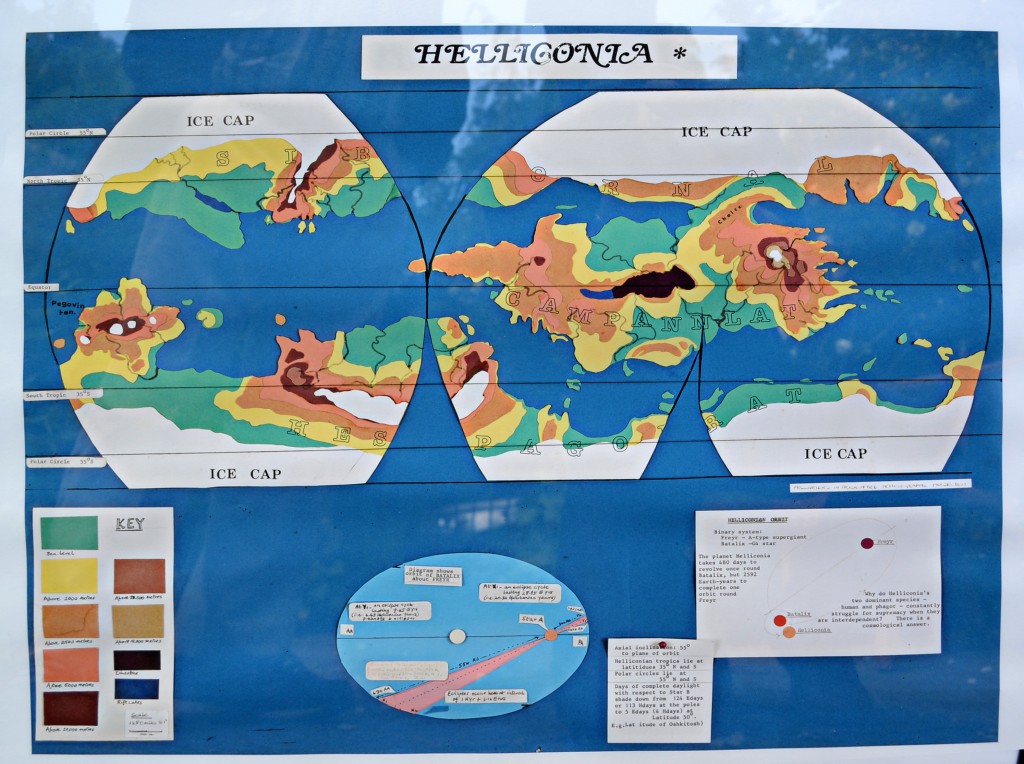

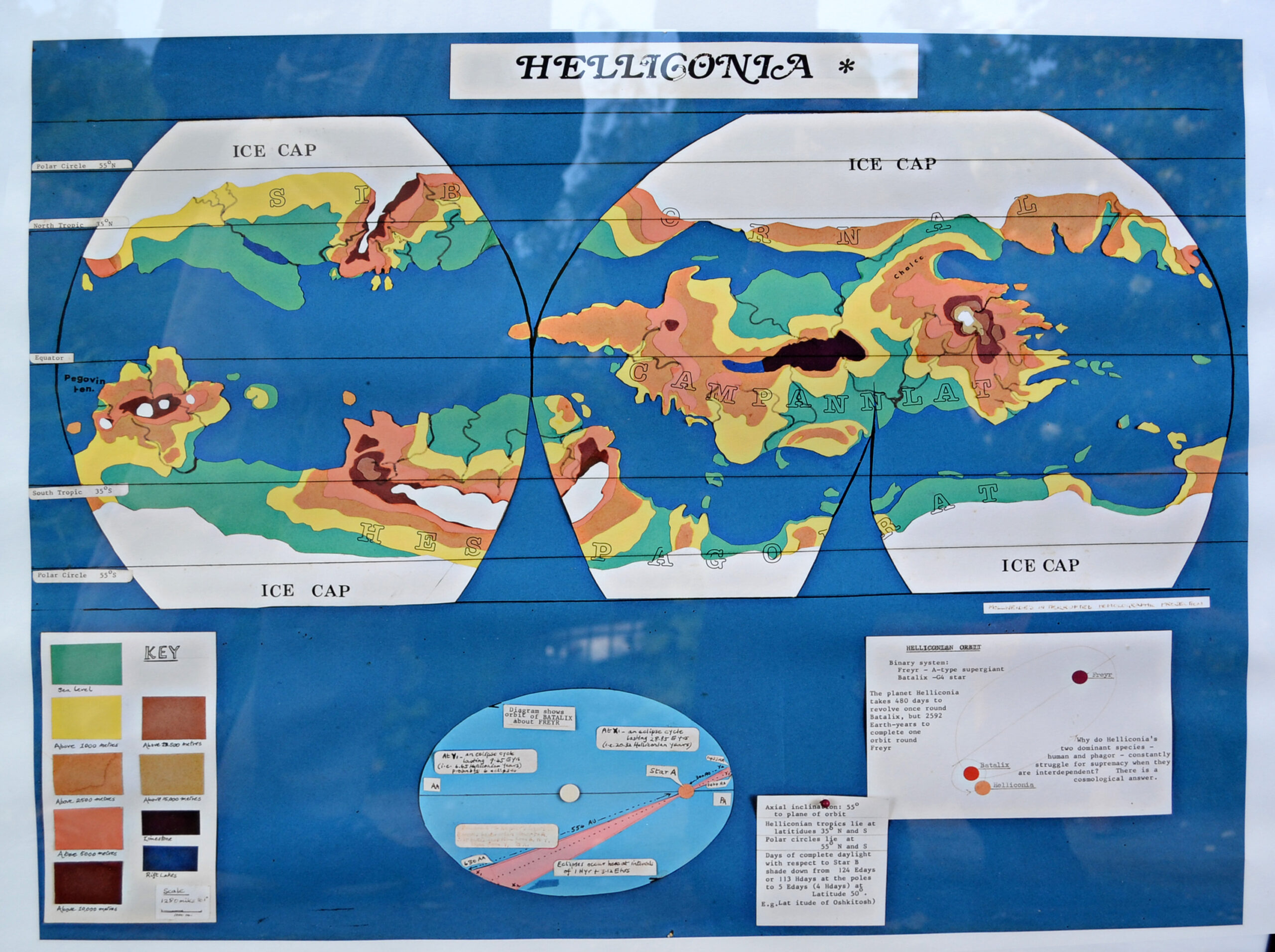

The creative part of the brain works at its own pace, and in its own way. In the summer of 1977, I wrote a letter to a friend setting forth in outline how I imagined conditions would be for a human-like race inhabiting a planet resembling Earth with a year which endured for several thousands of ordinary years. `Let’s say this planet is called Helliconia,’ I wrote, on the inspiration. The word was out, the name named. The process of conjuration had begun. From then on, I had to proceed consciously.

I worked with great concentration and dedication. The novel was to be in three volumes, with each volume completed in little more than eighteen months, averaging approximately 150,000 words per volume. The whole story was finished by the end of June 1984.

It was clear from the start that I would need advice for all the disciplines needed to fortify the narrative: history, biology, philology, and so forth. At the basis of everything, the astronomical and geophysical aspects – the details of the Helliconian binary system – had to be as correct and current as could be. Today’s theories were wanted, not yesterday’s.

So I consulted the various authorities whose names are acknowledged in the novels. Most of them entered into the game of Helliconia readily, and had fruitful suggestions to make. Most specifically, it was Iain Nicholson’s description of the binary system and how it came about which opened up what I regard as one of the most profound themes of the novel, the process of enantiodromia, by which things constantly turn in to their opposites; knowledge becomes by turns a blessing and a curse, as does religion; captivity and freedom interchange roles; phagors become by turns conquerors and slaves. As a means of making concrete this amorphous but deeply felt theme, the binary model was ideal. (Only later did I turn back to one of my short stories, `Creatures of Apogee,’ to perceive that I had already deployed the process on a miniature scale.)

![]() Ambition grew in me to construct a great story, a new kind of scientific romance which would look substantial even when set beside the epics of the science fiction writer I most admire, Olaf Stapledon.

Ambition grew in me to construct a great story, a new kind of scientific romance which would look substantial even when set beside the epics of the science fiction writer I most admire, Olaf Stapledon.

A number of factors fostered this determination. I will mention only a general and a personal one.

The general first. All was not well with the science fiction field in which I had worked so long. I had been proud to be considered a rule breaker, a renegade, a man who followed his own star regardlessly. My strong opinions in particular those concerning the impossibility of exceeding the speed of light in a heavier-than-light vessel and the improbability of finding intelligent life elsewhere in our galaxy had made me enemies. Nevertheless I saw myself as part of a field which had its own dynamism, and within which some sort of rational debate went forward.

Now the massif central of science fiction was crumbling. SF which adhered to rational posits was becoming rarer. Younger writers, particularly in my own country, were hedging their bets by writing a form of science fiction which might, with luck, pass for ordinary fiction, or by creating texts which lodged themselves comfortably in a nostalgic past rather than the future. Everywhere, everyone was writing fantasy; novels abounded in which the hero or the hero with his miscellaneous gang is impossibly heroic, where what prevails is an air of general implausibility or, to give implausibility its euphemistic name, magic. In short, it seemed as if the rational was out of favour, along with the ancient art of story-telling.

This crisis may be attributed to several causes, some working within the medium, some outside. The older type of science fiction, looking ahead to an expanding future, is difficult to write in the depressed decade of the eighties, when the world is undergoing recession. ‘the insistent threat of nuclear warfare, too, makes us appear trivial or falsely optimistic if we write about a prosperous future. With the Third World on our conscience, dreams of technological glory ahead are apt to ring hollow. Too many schemes which once seemed excitingly utopian have ended in disaster and disarray, like the scheme to `develop’ (a word regarded with scepticism nowadays) the Amazon basin.

Science fiction writers are demoralised by the megabuck-earning SF films of recent years, and often try to imitate their follies. While the writers of rubbish can always eke out a living, middle-echelon writers are being squeezed hard by changes in the market and marketing philosophy. The opportunity extended to famous writers of an older generation, such as Asimov, Clarke, and Heinlein, to turn out poor imitations of earlier work and he overpaid for it is also demoralising.

To the personal factor. Even my earliest novels, such as Non-Stop, Hothouse, and the chronicle-novel (as its first publishers called it) Galaxies Like Grains of Sand, have reflected my concern for the paradox that mankind, a part of nature, has seen itself apart from nature, opposed to nature. It is a faulty perception which will lead to disaster, and has led to disaster. When I defined SF as `Hubris clobbered by Nemesis,’ I was thinking of this divorced element in the human psyche, which I have in the past defined in Toynbeean terms as the division between the head and heart.

This fatal divorce is something we suffer from as individuals, and not merely as a species. In the present day we seem to have, in general, lost an awareness of our closeness to the earth. Our perspectives have narrowed. Our reason has not helped us to see that we are sustained by a number of non rational sources such as our instincts, our sense of empathy with others, and all those pleasant promptings about life, birth, death, and the mythological level of life (in short, those numinous qualities which were once labelled `God,’ or something similar, in times when the heart had dominance over the head). The cities have spread the poison. We are flimsier creatures than we should be. We can’t see the stars for street lamps. We live in a world of fences. We build the fences, to hide our incompleteness.

Such intimations came to me more clearly when I found that my existence had passed through a disturbing phase into one more richly productive, which Carl Jung refers to as `individuation.’ I felt that what was perceived more clearly might be expressed more clearly, and that this time I might add a diagnosis. Whether I was right or not, I was certainly confident.

So there was the will to make a general romance about Helliconia of, let’s say, a semi-scientific nature. And there was the will to go beyond that and construct a drama which could accommodate my diagnosis of the world’s ills. But more importantly, there was the will of the novelist to seize upon the large stage of Helliconia to tell that drama in the most effective way.

![]() At first I had some hope of cramming everything into one book. This soon proved to be impossible. To give any adequate idea of the scale of Helliconian life, then at least three points sample points in the mighty arc of the Great Year had to be taken and displayed with all the vigour at my disposal. That meant telling stories about characters to which an ordinary reader might lend sympathy: people not given over to heroics, though sometimes to heroism; not faultless people, set apart by virtue; but people, men and women, caught in the toils of life, often unclear about where they were going, and involved in their feelings for one another; in short, courageous people without a great deal of insight. And these people would be shown in contrast to the gigantic background of their planet at periods when both the climate and history were undergoing change.

At first I had some hope of cramming everything into one book. This soon proved to be impossible. To give any adequate idea of the scale of Helliconian life, then at least three points sample points in the mighty arc of the Great Year had to be taken and displayed with all the vigour at my disposal. That meant telling stories about characters to which an ordinary reader might lend sympathy: people not given over to heroics, though sometimes to heroism; not faultless people, set apart by virtue; but people, men and women, caught in the toils of life, often unclear about where they were going, and involved in their feelings for one another; in short, courageous people without a great deal of insight. And these people would be shown in contrast to the gigantic background of their planet at periods when both the climate and history were undergoing change.

From the start, it was apparent that my characters were going to suffer vicissitudes even greater than those in my previous novels. Readers know what critics often forget, that it is oddly comforting to read of fictional suffering. Nevertheless, I wanted to reward my readers with what optimism was inherent in the system: the possibility that human life might be happy, and the way there. Since I had reached a period of stability and happiness myself, that way could be found, and finding it shaped the pattern the overall story took.

It all sounded straightforward, once I had familiarised myself with my own intentions. But before I began to write, I decided to make the game a little more complex by staging the drama on more than one plane. There should be five layers to this cake.

We should explore life on Helliconia. Fine. But this was without relevance unless we also learnt something about life on Earth. And, as an intermediary between the two planets, we must have the Earth Observation Station, orbiting Helliconia, in which human beings are suspended like souls in limbo. But to venture further, to the fourth layer, let’s see what happens to the Helliconians when they die, let us pursue them into the afterlife.

And, since in large measure this is a drama of evolution, let’s see what kind of post-Christian gods control Helliconia and Earth. So we come to the highest level, the level of the tutelary deities, who emerge fully in the third volume.

Once I began writing, all else was forgotten but the interest in the story, the saga of Yuli wandering from the snowy wilderness into the dark citadel of Pannoval: then to be followed by the growth of Embruddock, and the people who live there, the dedicated Shay Tal, the intransigent Aoz Roon, diffident Laintal Ay, and all the others, whose lives are lived out as Spring unfurls and veldt emerges from the snow-plains.

In the second volume, as Helliconia and its sun Batalix draw nearer to Freyr at the time of perihelion, the drama is a more subtle and complex one, concerning the holding of territories and kingdoms, the triumph and eclipse of religions, and the difficulties of a headstrong king divorcing his beautiful queen, the Queen of Queens, in order to make a dynastic marriage with a child. This particular story, by the way – or the germ of it – was borrowed from the history of the early Serbian state and the reign of the doomed Nemanijas. King Milutin took as his fourth wife the child Simonida, daughter of the Byzantine Emperor Andronicus. In Thessaloniki he was married to his six-year-old bride. You can still see Simonida staring out at you, tense and doll like, from frescoes in Jugoslavia, most notably in the lovely monastery of Gracanica. But child marriages were common in the Middle Ages.

The second volume has the richest prose. Among other things, I read and attended performances of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream to prepare myself for its writing.

The final volume relates what happens in the northern hemisphere of Helliconia, Sibornal, after a campaign, when the army returns home with the plague in its ranks. The central character is Luterin, a young man who does not understand the truth about his parentage – an echo of the situation regarding humanity itself. He is infatuated in turn by two ladies, his intended bride, Insil Esikananzi, and a slave woman whose husband he has killed, Toress Lahl. The novel has its strong romantic elements, although the ending is anti-romantic; this is the case with the first two volumes also.

Helliconia is presented as a strange and wonderful planet. So it is. But so is Earth, and there is little that happens on Helliconia which has not happened in one form or another on Earth. The one major difference is the existence on Helliconia of other intelligent or semi-intelligent species: most notably the phagors, that ancipital race perpetually warring with humanity for possession of the globe.

![]() Although deadly enemies, phagors and humans exist in a commensal relationship with each other. Much of the story is taken up with this painful relationship, which must be broken and yet would be fatal to break. On Earth we have no phagors, only the animal sides of our natures, with which we are similarly at war, and with which we must come to some kind of agreement. This problem, exciting as any encounter with a mounted phagor, finds explicit place in the final volume.

Although deadly enemies, phagors and humans exist in a commensal relationship with each other. Much of the story is taken up with this painful relationship, which must be broken and yet would be fatal to break. On Earth we have no phagors, only the animal sides of our natures, with which we are similarly at war, and with which we must come to some kind of agreement. This problem, exciting as any encounter with a mounted phagor, finds explicit place in the final volume.

For me, one of the happiest moments in the whole story is when a terrestrial human being, one of our descendants, points to the whereabouts of Helliconia in the tropical night sky, in the constellation of Ophiucus. This is one way of indicating that the book is not a fantasy. Helliconia has, in Shakespeare’s phrase, `a local habitation and a name.’ It is a world where you can be flung into prison for debt. For these reasons, and be cause of the strong sub theme of evolutionary progression, I have used H. G. Wells’s term and called the book `a scientific romance.’

But sufficient room has been left between the lines for every reader to make what he will of it. Half the attraction of having such a broad canvas is that it can be filled with terrors and adventures and excitements.

Readers ask if everything in all three volumes was planned before I began to write. The answer must be no. I knew what I wanted to happen and where I had to go. And I had the guidelines suggested by my experts. But most of it was my own devising, and I allowed myself to surprise my self day by day.

Eventually I got, with some astonishment, to where I intended. But during my seven years of work, the world itself had moved on. There were two areas of scientific discovery in particular which brought interesting news.

Our sun is believed* to have a companion, dubbed Nemesis, which at its nearest comes within half a light year of Earth. Its passing disturbs the Oort comet cloud, so that Earth is bombarded by cometary material, the result of which is a kind of short and natural `nuclear winter,’ with a cooling of Earth’s surface sufficient to bring about the extinction of various phyla. These conclusions are supported by findings in the fossil record, with mass extinctions occurring every 26 million years (the dinosaurs being victims of the most famous extinction), and by patterns of impact craters on the Earth’s surface.

Other research, into the likely effect of detonation of nuclear weapons in our atmosphere, has led to the coining of the unpleasant if picturesque phrase used in the preceding paragraph, nuclear winter. The impact of even a `modest’ nuclear war, say something in the region of ten thousand megatons, would be such that the filth released into the upper layers of the atmosphere would precipitate changes in the climate of the northern hemisphere. Photosynthesis could not take place. Not only human beings but trees and many other phyla would die. Europe might come to resemble Greenland or, at best, a chilly steppe. Nor would these effects necessarily remain contained within the atmospheric circulation of the northern hemisphere.

For neither of these two interesting advances in knowledge had I, sitting in my study in Oxford, originally planned. Yet it could not be said that I was unprepared; my narrative and its concerns were such that both sets of findings settled readily into the script! Indeed, the nuclear winter scenario went to reinforce the metaphor of Helliconia’s harsh seasons.

Encouraged by this act of serendipity, I determined to go further than intended, and develop the hypotheses of James Lovelock to some degree; thus my novel would fulfil all the obligations of true science fiction by encompassing, not only scientific knowledge still under debate, but speculation based on that knowledge. Time will test the accuracy of my guess. At least the guess is an optimistic one. And it would be a pity to end this three-volume parade of gallantry and folly on anything but an optimistic note.

*This hypothesis has already been challenged by later ones.

[…] Could the fossil on the Martian meteorite could be a tiny autocell? If so this also effects Gaia theory (something also close to my fathers heart and writing such as his Helliconia trilogy). […]

[…] the author of science fiction classics including Non-Stop, Hothouse and Greybeard, as well as the Helliconia trilogy, which his agent said bridged “the gap between classic science fiction and contemporary […]

[…] Alldis (another recent decease), for the Helliconia novels. OK: my link there is anything North Norfolk-born, but also because of an unpleasant […]

[…] fuente: Web oficial de Brian W. Aldiss […]