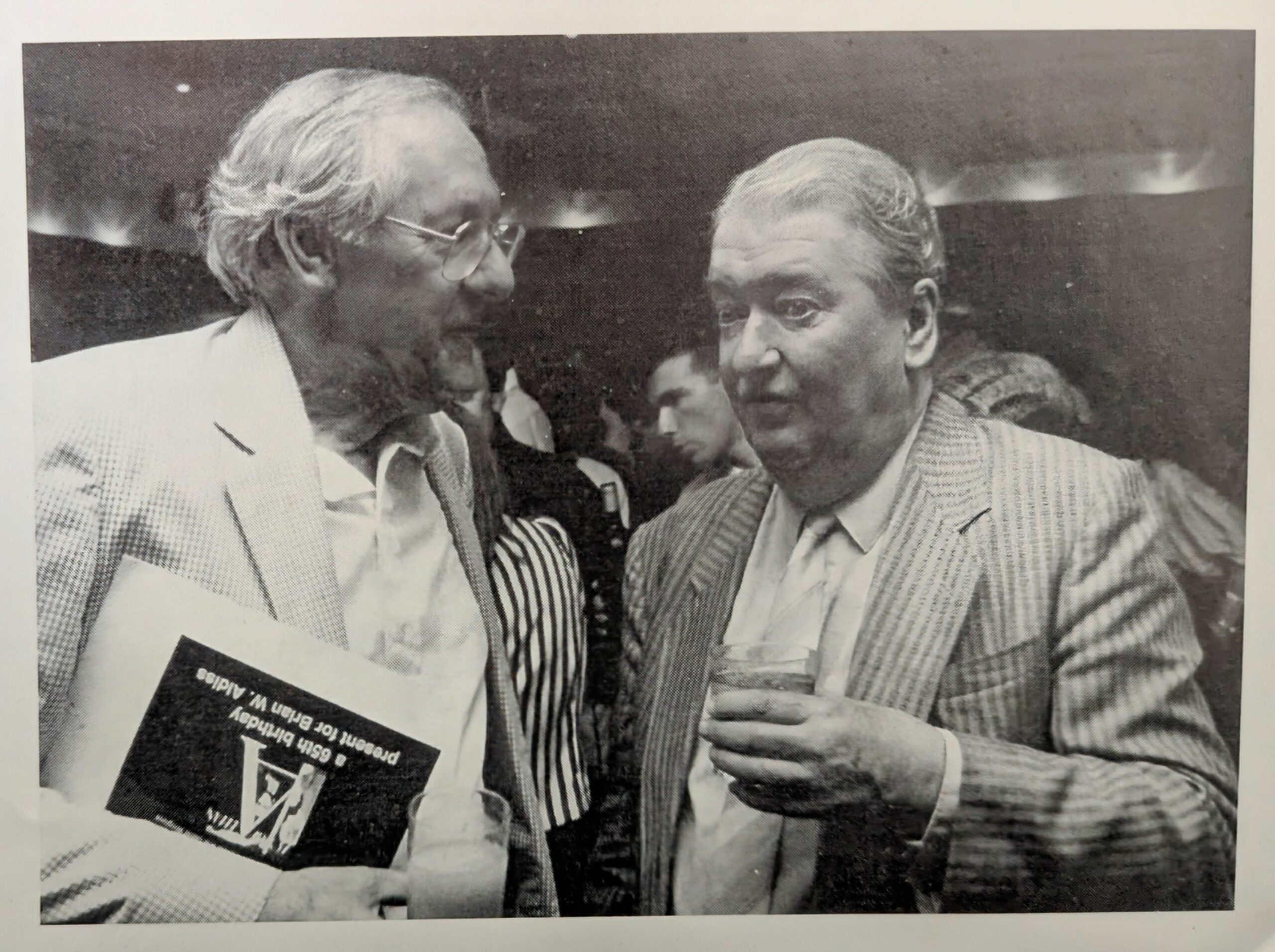

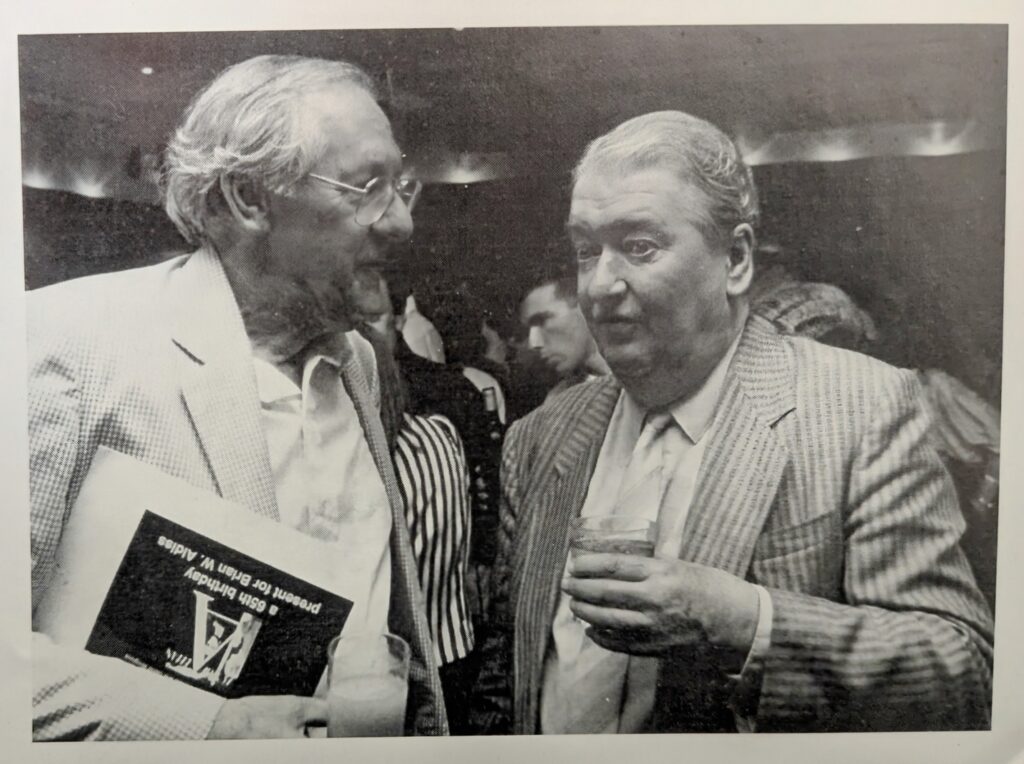

Kingsley, born in 1922, came up to St. John’s College, where he met Philip Larkin. They remained friends for life. Kingsley was good at friendship. I am convinced that it was Kingsley who got me a place in ‘Who’s Who’, but he was not the sort of bloke who would sneak round later, saying, ‘Look, old chap, I’ve managed to wangle your name into ‘Who’s Who’ – thought you’d like it…’

Kingsley’s first novel, Lucky Jim was an immediate and immense success. This was after he had gone down. “Lucky Jim – it’s me,” said another friend of mine, Eddie Cooney. And whoever we were, we felt Kingsley had caught something of us.

In those early days, Kingsley was invited down to Oxford to give a lecture at Exeter College. I went along to a lecture room in the Turl. Kingsley spoke in a lively way, rather than an Oxford way. When his talk was finished, ‘any questions’ were asked for. A silence fell. It was embarrassing for Kingsley. I stuck up my hand and asked if he thought one might make a living from writing science fiction. His answer was Yes, sort of, with luck, and so on. The function was over. As we trooped out of the room, Kingsley asked me my name. I told him.

“My God,” he said. “You wrote ‘Outside’, Come and have a drink.”

It’s hard to believe that a friendship ever began on better terms.

And for those who still have not read that story, I will say that the opening line is “They never went out of the house”.

But we all sort of liked science fiction. Kingsley later wrote SF himself (to be mocked by Mrs Thatcher for it).

For much of this time, I was living either in one or one-and-a-half rooms. Kingsley was doing rather better. We were both fond of drinking and women. I became involved with these delights. ‘The Pill’ had come into vogue; which meant that for women there was less anxiety regarding falling pregnant. They became much more liberal with their favours while chaps went on being their usual awful selves.

Kingsley was immensely funny. He had a talent for minutely impersonating others . So that if Crispin, say, left the room, Kingsley would immediately become Crispin, saying silly things. We were convulsed – but it did make one reluctant to leave the room for a pee.

Kingsley and wife Hilly moved to Cambridge, to a rather smart house. I would go by train to see him occasionally, but that wretched fellow Dr Beeching abolished the quaint little line which ran between Oxford and Cambridge, calling at villages one imagined were named after some local lord’s Edwardian mistresses – Fenny Compton, and so forth.