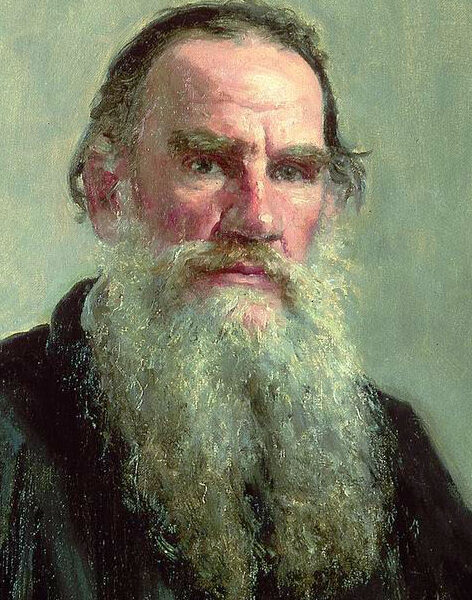

Count Leo Tolstoi’s final novel was published in installments throughout 1898, in a magazine. In fact, in several magazines. Tolstoi was seventy years old in an exhausting year. Tolstoi had to check cuts made in his work by censors, week after week. Censors were not the writer’s only problem; closer to home, Sonya, Tolstoi’e wife, was unhappy about the sexual passages in the book.

Yet slowly this great oak spread its roots. A recent biographer of Tolstoi, Rosamund Bartlett, describes how it came about that an English and an unexpurgated Russian version were simultaneously published. Resurrection in these forms were reprinted five times in 1900. These editions were smuggled into Russia ‘in enormous quantities’. The success of “Resurrection”, says Bartlett, ‘was phenomenal and unprecedented’,

Nowadays Tolstoi is available in Penguin Books, the most recent editions of “Resurrection” being, as far as I know, are translations by Rosemary Edmonds and now by Anthony Briggs,

This capacious story certainly has what we understand as a plot, but is best regarded as a series of reflections. perceptions, and condemnations,

Tolstoi’s early disillusion came in a visit to Kiev, which Bartlett terms the cradle of Russian civilization. Pilgrims in their hundreds of thousands crowded in to worship at the ancient monastery, thereby assailing traditional peace and silence of worshippers. Tolstoi was turned away. That great mind started to work against the Church; he began his own translation of the Gospels.

We can see this is to be no light-hearted novel of escapades and romances. It carries an immense burden of life and moral instruction, from its very first paragraph onwards, It contains many events and characters, going into prisons, dining with the wealthy, confronting the destitute. Yes, this is a masterpiece, yet in our age of trivial pursuits it suffers from neglect.

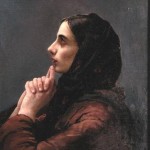

Count Dimitri Nekhlyudov is the troubled aristocrat who carries the story forward. This story begins with a sketch of young Maslova, daughter of a serf, She finds work with two old ladies of good breeding, living together. They cultivate Maslova ; her situation under the family roof is fortunate but uncertain.

Then along comes young Nekhlyudov and falls in love with her.

Nekhlyudov’s stay with his aunts is brief. He enlists in the Army and enjoys the Army’s roughness and debauchery. After some years ‘of dissolute, luxurious living’, he again visits his aunts. There is Maslova, still attractive. They are drawn to one another, and our brave soldier ‘enjoys the full fruits of love’, as it says here, with the young woman.

When the aunts find out that their servant is pregnant, they sack her. Maslova becomes a prostitute, and works in the city, later to be accused of murder. Her problems obsess her seducer

Not all is gloom. Here is a brief extract from the time of Easter, when Nekhlyudov joins in the church celebrations.

‘Everything was festive, solemn, happy and beautiful; the clergy in their silver cloth vestments with gold crosses; the deacon and the sub-deacon in thei silver and gold surplices; the choir singers in their best clothes, with their hair well oiled; the gay dancing melodies of the Easter hymns; the continued blessing of the people by the clergy with their triple flower-bedecked candles; and the ever-repeated salutation: ‘Christ is risen! Christ is risen!’

‘It was all lovely, but best of all was Kadusha in her white dress and blue sash, with the little red bow on her dark head, and her sparkling rapturous eyes…

‘For her glittered the gold of the ikonostasis; for her burn- ed all the candles in the candelabrum and the candle-stands; for her the joyful chant rang out, ‘The Passover of the Lord, Rejoice, O ye people!…

‘During the pause between the first and second service, Nekhlyudov went out of the church. The people stood aside to let him pass, and bowed. He stopped on the steps. The beggars instantly clamoured round him and he gave them all the change he had in his purse, and walked down the steps.’

This story marks an end to Tolstoi’s long career as a writer, and during its immense unwinding he recalled a tale told him previously. Anthony Briggs gives an account of this in the introduction to his translation of ‘Resurrection’.

Nekhlyudov is called to jury service. There are vexing delays before the jury is called. And there the Count finds Maslova, a prisoner at the bar, charged with the murder of a client.

This is the pendulum on which the whole book swings.

Maslova is wrongly charged, through carelessness, and is to be exiled to Siberia, a word and region as awful then as it remains.

Nekhyludov is overcome with remorse and decides he must marry Maslova. She turns him down; he seduced her when she was innocent: now he expects her to save his soul. She will have none of it.

So we find him visiting wretched filthy prisons. He also visits his peasants living, working, starving, on his own lands, in order to hand the land over to them- in other words, to free those who labour for his benefit; which proves difficult; the peasants have been cheated often enough; they draw back, suspecting trickery.

So this grand dark morality-tale unwinds. Near its closure comes a great extended series of scenes as hordes of convicted people, Maslova among them, are marched off to prepare for their journey to Siberia.

‘It had become very hot. There was no wind., and the cloud of dust raised by thousands of feet hovered all the time above the prisoners as they moved down the centre of the road…

‘Line after line they advanced, strange fearful creatures dressed alike, thousands of feet shod alike, all in step, swinging their arms as though to keep up their spirits. There were so many of them, they looked so exactly alike and their circumstances were so extraordinarily odd that to Nekhlyudov they no longer seemed to be men…’

The authority of such scenes is undeniable. And unforgettable.

And finally? Nekhyludov finds among the uncertainties of life a degree of comfort in St Matthew’s Gospel.

“Resurrection”, with its bold criticisms of many seemingly stable factors in Russian life, was received with excitement, as it emerged in print from 1898 onward.

Tolstoi had a final quarrel with his poor wife and took to the railway to travel to the South. He became ill on the train, and was carried to the station-master’s hut, where he passed away. The station was besieged by thousands of people; among them happened to be one man with a movie camera. So we can still view that crowd, that railway station, that notable death.

Sweetness and light among shame and confusion. The greatest of all novels is Leo Tolstoy’s final novel, “Resurrection”. Its effect upon a reader is immense and immediate. Even after eight readings of various translations, I continue to feel its spell and admire its complexity.

“Resurrection” is the story of a man tormented by the injustices of the world about him, who is at the same time tortured by his own self-indulgence. A reader likes but fears him, since it is possible we may find our own weaknesses depicted in these pages.

This battlefield of literacy was published serially first in 1899. Nothing else among Tolstoy’s writings has excited such extremes of denigration and approval. I bow to the strength of its commitment, and to Tolstoy’s powers in his old age, like a formidable engine that elevates us.

Count Nekhlyudov, the central character of this huge chronicle, stays in his youth with two old aunts who have engaged a charming young woman, Maslova, as companion. Young Nekhlyudov falls in love with Maslova, and she with him. He joins the Army and becomes a general-roust-about. Returning to his aunts’ house after a couple of years, he seduces Maslova, making her pregnant. (Here is an echo of the author’s seduction of his sister’s maid, long ago.)

Later comes the scene where he is appointed to jury service. To his horror, he finds that the prisoner on trial for prostitution and murder is Maslova, now much deteriorated. Everyone bar Nekhlyudov is indifferent to the girl’s fate, so that we find that Maslova is to be exiled to Siberia. He tries to marry her but she refuses him.

“You had your pleasure from me in this world, and now you want to get your salvation through me in the world to come!” Although snubbed in this way, Nekhlyudov does everything within his power to protect and save her from unjust punishment.

Nekhlyudov enters stinking prisons while trying to help Maslova. Tolstoy had himself visited such prisons; innocent and guilty alike are incarcerated.

Iniquity and inequality fall under Nekhlyudov’s inspection. He attempts to give his land to the peasants farming it. They will not have it – they have been cheated by owners often enough. Starving men labour among the great fields. Their animals starve with them.

Towards the end, ranks of prisoners, fresh from freezing prison cells, are forced to march through the streets in a heat wave, in some cases being struck down by the heat, and dying; or piling into crowded trains, leaving behind such civilisation as there was.

‘All this happened,’ Nekhlyudov says to himself, ‘because all these people – governors, inspectors, police-officers and policemen – consider that there are circumstances in this world when man owes no humanity to man.’

This brilliant, troubling novel at first out-sold Tolstoy’s earlier novels, even ‘War and Peace’. It was criticised for its outspoken contents. It remains a grand panorama of discontent.